Distributed Lock with Redis - Critique

Table of Contents

TL;DR: Redis is an AP system, not a CP system. It cannot guarantee strong consistency. For high-concurrency use cases, expect potential data races when using Redis. Consider systems that provide strong consistency (e.g., etcd, ZooKeeper) if you need strict guarantees.

The Single Instance Lock⌗

In the previous post, we explored how to implement a distributed lock using a single Redis instance. We addressed the question: what if the client crashes? But we left one critical question unanswered: what if Redis itself fails?

This post examines that question, and why the answer is more nuanced than you might expect.

Redis is an AP System⌗

If you’re unfamiliar with what an AP system means in the context of the CAP theorem, you can read my article here.

In short, an AP system prioritizes availability over data consistency across multiple nodes. When a failure occurs (e.g., network partition, node crash), the system remains available but may serve stale or inconsistent data.

Redis uses asynchronous replication by default in a primary-replica architecture. This means writes acknowledged by the primary are not guaranteed to be replicated to replicas before the acknowledgment is sent to the client.

Here’s the problem for distributed locks: if the Redis primary crashes after acknowledging a lock acquisition but before replicating it, a replica promoted to primary won’t have the lock data. Another client could then acquire the same lock, violating mutual exclusion. While Redis has mechanisms to resync data after failover, the newly promoted primary may still operate on stale state during this window.

The Split-Brain Problem⌗

Even with multiple Redis instances and the Redlock algorithm, another fundamental issue remains: split-brain.

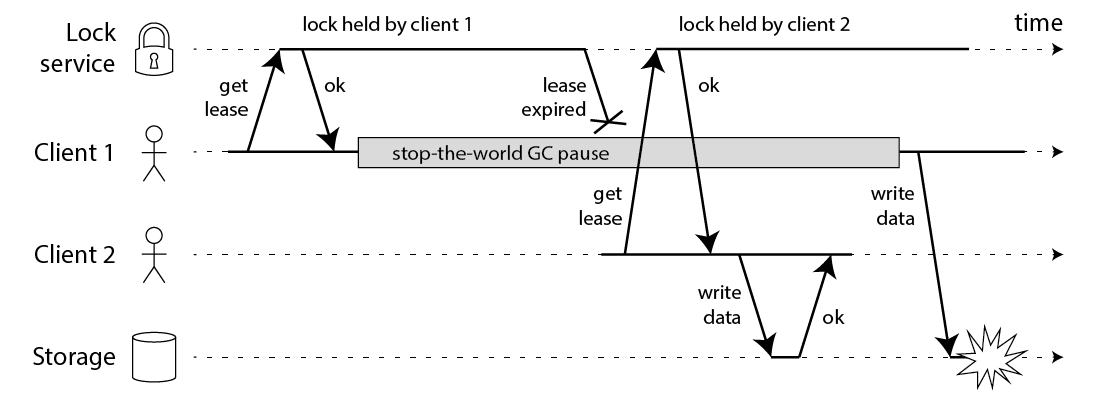

Consider this scenario: Client A acquires a lock and begins processing. Then it gets paused, perhaps due to a long garbage collection (GC) pause, a VM suspension, or network latency. While paused, no lock extension happens, and the lock’s TTL expires. Client B now acquires the same lock and starts working on the shared resource. When Client A eventually resumes, it has no idea its lock expired and continues operating as if it still holds exclusive access.

Now both clients are modifying the same resource simultaneously, a classic split-brain scenario where two processes believe they have mutual exclusion, but neither actually does.

Martin Kleppmann explored this problem in depth in his post How to do distributed locking. His key insight: Redlock makes dangerous assumptions about timing. It assumes bounded network delays, bounded process pauses, and synchronized clocks. Assumptions that distributed systems regularly violate.

Image credit: Martin Kleppmann

Kleppmann’s recommended solution is fencing tokens: a monotonically increasing number issued with each lock acquisition. The storage system rejects any operation with a fencing token older than the last one it has seen. This way, even if a paused client wakes up late, its stale token will be rejected.

Note: A monotonically increasing number is one that only ever goes up, never down. Each new value is strictly greater than all previous values (e.g., 1, 2, 3, …). This property is essential for fencing tokens because it allows the storage system to determine ordering: a higher token always means a more recent lock acquisition.

Examples of monotonic ordering mechanisms in distributed systems include:

- Lamport clocks: a simple logical clock that increments on each event

- Vector clocks: an extension that tracks causality across multiple nodes

- ZooKeeper’s zxid: a 64-bit transaction ID that increases with every state change

- Database sequences (e.g., PostgreSQL’s

SERIAL, MySQL’sAUTO_INCREMENT): centralized counters that guarantee uniqueness and ordering

Redis’s lack of a native monotonic counter makes implementing true fencing tokens difficult. Combined with the asynchronous replication we discussed earlier, this makes Redis unsuitable for distributed locks that require strong consistency guarantees.

That said, for many applications where occasional race conditions are tolerable or where other safeguards exist (e.g., idempotent operations, database-level constraints), Redis locks, whether single-instance or Redlock, remain a practical and performant choice.

Alternative Solutions⌗

If you need strong consistency guarantees for distributed locking, consider these alternatives:

-

etcd: Provides a built-in lock API with native lease-based fencing. Built on Raft, a consensus algorithm with formal correctness proofs, etcd guarantees linearizable operations across the cluster.

-

ZooKeeper: Offers distributed lock recipes using ephemeral sequential nodes. It uses

zxid(ZooKeeper Transaction ID) as a globally ordered, monotonically increasing counter that can serve as a fencing token. ZooKeeper uses the ZAB (ZooKeeper Atomic Broadcast) protocol for consensus.

Both systems are CP (Consistency + Partition tolerance) in CAP terms, sacrificing availability during network partitions to maintain strong consistency. This is the fundamental trade-off: Redis gives you speed and availability; etcd/ZooKeeper give you correctness guarantees.

References⌗

- Redis - Redis replication model

- How to do distributed locking - Martin Kleppmann critique on Redlock

- Is Redlock Safe? - antirez (Redis creator) counter argument for Redlock usages

- etcd - etcd Concurrency API

- ZooKeeper - ZooKeeper Locks Recipe

- Raft - The Raft Consensus Algorithm